The Grand Staff

::

|

Key words:

note

note sign

pitch name

A B C D E F G

pitch class

B & H

octave equivalency |

| 1 |

Naming the Notes

notation, notazione (Italian f.), Notation (German f.), Notenschrift (German f.), notation (French f.), notacion (Spanish f.)

note, nota (Italian f.), Note (German f.), note (French f.), nota (Spanish f.)

Music is composed of discrete elements or sounds called notes.

Musical notation describes these elements in terms of their pitch

(related to the note's frequency), their arrangement in time (when they

begin to sound), and their duration, (how long they should last). The

signs we use are called note signs or notes.

In English-speaking countries, in a general sense, a series of rising

pitches are named using the first seven letters of the Roman alphabet:

A B C D E F G.

The sequence continues indefinitely, restarting from A when moving beyond G, or moving from A to G when moving below A. By convention the notes rise in pitch as one moves from A to B to C, etc.

We will learn later that there are additional notes where, using A as an example, the note a semitone (half note) higher bears the additional name 'sharp' (thus A sharp) while the note a semitone (half note) lower bears the additional name 'flat' (thus A flat).

In the Netherlands, the letters A to G are also used, but

otherwise the 'Dutch' system follows the 'German' system, so-called

because it originated in Germany, which also uses H. We describe this system in section 3 below.

|

| 2 |

Unusual Note Naming Convention in Scottish Bagpipe Music

The bagpipe chanter has a range of nine notes commonly written as the sequence G A B C D E F G A, where A is the key note. In fact the notes C and F are C# and F#

(i.e. each sounding a semitone higher than written) but because in the

traditional way of playing the notes are never modified the notation

leads to no ambiguity. More recently players have begun to use special

cross-fingerings to flatten by a semitone the notes written C and F. Because bagpipe music has traditionally notated these two sharps as naturals, players now notate the 'flattened' notes as Cb and Fb, although they actually sounds as C and F respectively.

Reference:

|

| 3 |

The Notes B & H and Solfeggio

solfa, solfeggio (Italian m.), Solfeggio (German n.), solfège (French m.), solfeo (Spanish m.)

In almost all European countries, except those whose main language is

English or a Romance language, the 'German' system is used. This also

uses the letters A to G of the Roman alphabet, but reserves B for the note called B flat in the 'English' system, and uses H

for the note that is B natural (or just B) in the 'English' system. An

exception is found in The Netherlands, and more recently in Sweden,

where note names usually follow the 'English' system, using B, rather

than H, for B natural.

In the 'German' system, the names of notes that are a semitone (or half note) higher or lower, receive the suffixes -is (in Swedish, -iss) and, unless the note name is a vowel, -es (in Swedish, -ess) respectively. When the note name is a vowel (i.e. A or E) the suffix -es (in Sweden, -ess) is reduced to -s (in Sweden, -ss).

Chapter 9 includes a table detailing the various European systems. This system of suffixes is used also in The Netherlands.

Younger musicians in Sweden are now often taught a system similar to that used in the Netherlands, using b, biss and bess instead of the older h, hiss and b.

When musicians from different generations converse about note names

they have to agree which naming convention they will use. Magnus

Johansson tells us that he has students who use h when with him, and b in other circumstances.

In European and other countries whose main language is a Romance language, the pitch names are based on the solfeggio syllables:

do (or ut), re, mi, fa, so (or sol), la, si (or ti).

A Greek reader, Christos Kontas, informs us that the Greek pitch naming

system, which follows the Italian convention, is also based on the solfeggio.

References:

- personal communication from Christos Kontas on the naming of notes in Greece

- personal communication from Erik Magnus Johansson on the naming of notes in Sweden

|

| 4 |

Note Naming in Japan

Denise Owen who works in Japan has sent us the following note:

Both Japan and Korea use "fixed do" and pronounce them according to their language:

Japan: do, re, mi, fua (one syllable), so, ra, shi, do.

Korea: to, re, mi, pa, so, ra, shi, to.

(In Korean the initial "t" or "d" is unvoiced at the beginning of a word but voiced within the word.)

The iroha Japanese system that was used during and after WW II

when they didn't want to use Western names (though they were still using

Western-style music) starts on our pitch A and is:

i, ro, ha, ni, ho, he, to.

Thus, the treble clef is to-on kigo (the sound of to clef) and bass clef is he-on kigo (the sound of he clef).

Sometimes keys are named in orchestral movements and such according to this system: (ha choucho = C major, ni tancho = d minor).

Otherwise keys are generally named according to the German system.

Guitar players use the English letter system in Japan.

Conservatories use the German system.

Elderly people and some music theory (for example, clefs naming) still sometimes use the iroha system.

And "fixed do" is taught in schools.

References:

|

| 5 |

Pitch Class and Octave Equivalency

The human ear tends to hear notes an octave apart as being essentially

"the same". For this reason, in the Western system of music notation,

such notes are given the same pitch name and are said to be members of

the same pitch class — thus, the name of a note any number of octaves above or below A is also named A and all As are members of the pitch class A. This is what we call octave equivalency, and is closely related to the concept of harmonics, a subject we will consider later in lesson 27.

References:

|

|

Key words:

staff

stave

pentagram

brace

systemic barline

leger line

ledger line

diastematic

intervallic |

| 1 |

Staff or Stave

staff, stave, pentagramma (Italian m.), Liniensystem (German n.), Fünfliniensystem (German n.), portée (French f.), pentagrama (Spanish m.)

The note signs are placed on a grid formed of horizontal lines and spaces. This grid is called the staff or stave. The plural of either word is staves.

Although, in the past, staves could have many different different

numbers of lines, today the most common staff format has five lines

separated by four spaces and is know as the pentagram. When numbering the lines, it is a widely used convention to number them from the bottom (1) to the top (5) of each staff. The spaces between the lines are numbered too, again from the bottom (1) to the top (4).

We illustrate two common formats - the upper is usually

used for music where only one note is played or sung at any particular

time (for example, solo parts for flute, trumpet, violin, voice, etc.)

while the lower, two staves coupled together with a curly brace and a systemic barline, is used where many notes might be played at the same time (for example, solo parts for harp, piano, organ, etc.)

Music is read from 'left' to 'right', in the same direction as you are reading this text.

Music is read from 'left' to 'right', in the same direction as you are reading this text.

The higher the pitch of the note, the higher vertically the note will be placed on the staff. Such notation is called diastematic or intervallic.

|

| 2 |

Placing Notes on the Staff

Note signs

may lie on a line (where the line passes through the

note-head), in the space between two lines (where the note-head lies

between two adjacent lines), in the space above the top line or on the

space below the bottom line.

|

|

3 |

Leger or Ledger Lines

leger line, ledger line, linea aggiunta (Italian f.), Hilfslinie (German f.), ligne ajoutée (French f.), ligne additionnelle (French f.), ligne supplémentaire (French f.), línea adicionale (Spanish f.), línea suplementaria (Spanish f.)

Note signs outside the range covered by the lines and spaces of the staff are placed on, above or below supplementary lines, called leger (or ledger) lines, which can be placed above or below the staff.

Where two or more consecutive notes are written using leger lines, in

order to make the notes easier to read, the lines for each note are

always horizontally separated from those of the note following.

|

|

The Clef Sign

::

|

Key words:

clef

great staff

grand staff

great stave

grand stave

treble clef

bass clef

alto clef

middle C |

| 1 |

The Clef Sign

clef, clef sign, clef signature, chiave (Italian f.), Schlüssel (German m.), clef (French f.), clé (French f.), clave (Spanish f.)

To set the pitch of any note on the staff a graphical symbol called a clef (from the Latin clavis meaning key), clef sign or clef signature, is placed at the far left-hand side of the staff. The clef establishes the pitch of the note on one particular line of the staff and thereby fixes the pitch of all the other notes lying on, or related to, the same staff.

It is common practice to visualise each clef as a part of a much larger grid of eleven horizontal lines and ten spaces known variously as the Great Staff, Grand Staff, Great Stave or Grand Stave. Note the relationship between the Great Staff and most commonly used clefs, treble (top left in the picture below), bass (bottom left in the picture below) and alto (right in the picture below). It should be stressed that, historically, there never was a staff of eleven lines. It is solely a 'construct' or 'device' used by theorists to demonstrate the relationship between various staves and clefs.

The note we call middle C and which lies in the middle of the alto clef (for clarity, we have shown it in red), lies one line below the five lines of the treble clef and lies one line above the five lines of the bass clef.

|

|

The Treble Clef

::

|

Key words:

treble clef

F A C E

E G B D F

G clef |

| 1 |

The Treble Clef

treble clef, chiave di violino (Italian f.), chiave di Sol3 (Italian f.), Violinschlüssel (German m.), G-Schlüssel (German m.), clef de sol (French f.), clé de sol (French f.), clef de sol deuxième ligne (French f.), clé de sol deuxième ligne (French f.), clef de sol 2me (French f.), clé de sol 2me (French f.), clef de violon (French f.), clé de violon (French f.), clave de sol (Spanish f.), clave de sol en segunda (Spanish f.)

|

The treble clef is also called the G clef or G2

because the centre of the clef curls around the the horizontal line (2),

marked in red in the diagram below, associated with the note G above

middle C.The treble clef symbol is actually a stylised letter G.

The clef was originally known also as the violin clef and is

still called this in some countries. However, to avoid confusion this

name is best avoided in English as it can be confused with the French violin clef which is a different clef and is described in lesson 14.

|

|

When drawing this symbol freehand it is easiest to start from the bottom of the symbol and end with the curl around the G line.

|

| 2 | Naming Notes on the Treble Clef

The four inner spaces of the treble clef read upwards spell the word

FACE

.

The five lines read upwards spell

EGBDF

which you can remember using the phrase '

E

very

G

ood

B

oy

D

oes

F

ine

'.

The five lines read upwards spell

EGBDF

which you can remember using the phrase '

E

very

G

ood

B

oy

D

oes

F

ine

'.

|

|

The Bass Clef

::

|

Key words:

bass clef

G B D F A

A C E G

F clef |

| 1 |

The Bass Clef

bass clef, chiave di Fa2 (Italian f.), Bassschlüssel (German m.), F-Schlüssel (German m.), clef de fa (French f.), clé de fa (French f.), clé de fa quatrième ligne (French f.), clef de fa quatrième ligne (French f.), clé de fa 4me (French f.), clef de fa 4me (French f.), clave de fa (Spanish f.), clave de fa en cuarta (Spanish f.)

|

The

bass clef

is also called the

F clef or F4

because the two dots in the

clef

symbol lie above and below the horizontal line (4), marked in red

in the diagram below, associated with the note F below middle C.

The

bass clef

symbol is actually a stylised letter F where the two horizontal lines of the letter have been reduced to two dots.

|

|

When drawing this symbol freehand it is easiest to start from the

large dot and end with the tail at the bottom of the symbol - after

which one adds the two dots on either side of the F line.

|

| 2 | Naming Notes on the Bass Clef

The names of the bass clef lines

GBDFA

can be remembered by the phrase

G

ood

B

oys

D

o

F

ine

A

lways

.

The four inner spaces

ACEG

by the phrases

A

ll

C

ows

E

at

G

rass

or

A

ll

C

ars

E

at

G

as

.

The four inner spaces

ACEG

by the phrases

A

ll

C

ows

E

at

G

rass

or

A

ll

C

ars

E

at

G

as

.

|

|

The Alto Clef

::

|

Key words:

alto clef

C clef

viola clef

counter-tenor clef |

| 1 |

The Alto Clef

alto clef, viola clef, counter-tenor clef, chiave di Do3 (Italian f.), chiave di contralto (Italian f.), Altschlüssel (German m.), Bratschenschlüssel (German m.), clef alto (French f.), clef d'ut (French f.), clé d'ut (French f.), clef d'ut troisième ligne (French f.), clé d'ut troisième ligne (French f.), clef d'ut 3me (French f.), clé d'ut 3me (French f.), clave de do (Spanish f.), clave de do en tercera (Spanish f.), clave de contralto (Spanish f.)

|

The

alto clef also called C3

is one of a number that use the

C clef

symbol, so named because the the

clef

symbol is centered on the horizontal line (3), marked in red in the diagram below, associated with the note middle C.

|

|

The

alto clef

is also known as the

counter-tenor or viola clef.

|

|

Other Clefs

::

|

Key words:

soprano clef

mezzo-soprano clef

tenor clef

baritone clef

subbass clef

French violin clef

octave clefs

indefinite pitch clef |

|

The Score

::

|

Key word:

score |

| 1 |

The Score

score, partitura (Italian f., Spanish f.), Partitur (German f.), partition (French f.)

We meet terms like 'letter', 'word', 'sentence', 'line',

'paragraph', 'page', 'chapter' and 'book' when examining the structure

of a work of literature. Except in unusual circumstances, structure has

nothing to do with content.

In music we have terms that serve a similar function; so, for example, '

note

', '

bar

', '

line

', '

section

', '

movement

' and '

score

'. A composer creates a musical work, what we call a

score, which has various structural elements. We will learn more about these terms as we progress through our lessons.

|

|

Why Middle C?

::

|

Key words:

Guido d'Arezzo

gamut

solmization

Ut Queant Laxis

ut

re

mi

fa

sol

la

hexachord |

| 1 |

Solmization and the Naming of Notes

middle C, do centrale (Italian m.), eingestrichenes C (German n.), do central (Spanish m., French m.)

Why is middle C so named?

This interesting question was posed by a teacher in the United States of America.

The naming of the notes and position of middle C arise from the

way we set out our great staff. Guido d'Arezzo (c.995-1050) called the

first line on the lower staff by the Greek letter gamma. The lowest note in the scale was called ut and was placed on gamma. This first note was soon called gamma ut, which contracted to gamut. At some point, French musicians began referring to the whole scale (by then an octave) as the gamut,

a typical example of metonymy, the rhetorical or metaphorical

substitution of a one thing for another based on their association or

proximity. The term was next extended to refer to the musical range of

an instrument or voice. By the seventeenth century gamut was further generalized to mean an entire range of any kind.

Naming notes with syllables rather than letters is an example of

solmization. The syllables Guido d'Arezzo chose to use in the system he

developed in the eleventh century as an aid in the teaching of

sight-singing, namely ut, re, me, fa, sol, la, are taken from the hymn

Ut Queant Laxis Resonare Fibris. This is explained more fully in the entry for

Ut Queant Laxis Resonare Fibris

taken from the

Catholic Encyclopedia

to which we have added some extra detail.

|

| 2 | Ut Queant Laxis Resonare Fibris

Ut Queant Laxis Resonare Fibris

is the first line of a hymn in honour of St. John the Baptist. The

Roman Breviary divides it into three parts and assigns the first, Ut queant laxis, etc., to Vespers, the second, Antra deserti teneris sub annis, to Matins, the third, O nimis felix, meritique celsi, to Lauds, of the feast of the Nativity of St. John (24 June).

Durandus says that the hymn was composed by Paul the Deacon on a certain Holy Saturday when, having to chant the Exsultet

for the blessing of the paschal candle, he found himself suffering from

an unwonted hoarseness. Perhaps bethinking himself of the restoration

of voice to the father of the Baptist, he implored a similar help in the

first stanza. The melody has been found in a manuscript of the tenth

century, applied to the words of Horace's Ode to Phyllis, entitled

Est mihi nonum superantis annum.

The hymn is written in Sapphic stanzas, of which the first is famous in

the history of music for the reason that the notes of the melody

corresponding with the initial syllables of the six hemistichs are the

first six notes of the diatonic scale of C. This fact led to the

syllabic naming of the notes as Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, as may be shown by capitalizing the initial syllables of the hemistichs:

Guido of Arezzo, a Benedictine monk, showed his pupils an easier

method of determining the sounds of the scale than by the use of the

monochord. His method was that of comparison of a known melody with an

unknown one which was to be learned, and for this purpose he frequently

chose the well-known melody of the

Ut queant laxis. Against a common view of musical writers,

Dom Pothier contends that Guido did not actually give these syllabic

names to the notes, did not invent the hexachordal system, etc., but

that insensibly the comparison of the melodies led to the syllabic

naming. When a new name for the seventh, or leading, note of our octave

was desired, Erich van der Putten suggested, in 1599, the syllabic

Bi

of

labii, but a vast majority of musical theorists supported the happier thought of the syllable

Si, formed by the initial letters of the two words of the last line (

Si

because

J

and

I

were then both written

I

).

Guido of Arezzo, a Benedictine monk, showed his pupils an easier

method of determining the sounds of the scale than by the use of the

monochord. His method was that of comparison of a known melody with an

unknown one which was to be learned, and for this purpose he frequently

chose the well-known melody of the

Ut queant laxis. Against a common view of musical writers,

Dom Pothier contends that Guido did not actually give these syllabic

names to the notes, did not invent the hexachordal system, etc., but

that insensibly the comparison of the melodies led to the syllabic

naming. When a new name for the seventh, or leading, note of our octave

was desired, Erich van der Putten suggested, in 1599, the syllabic

Bi

of

labii, but a vast majority of musical theorists supported the happier thought of the syllable

Si, formed by the initial letters of the two words of the last line (

Si

because

J

and

I

were then both written

I

).

Si

was much later changed to

Te

by a Miss S. A. Glover and John Curwen so that each degree of the

scale would have a unique single letter abreviation used for written

notation. This was the start of the

movable doh

method of teaching which lasted in the UK for a hundred years (see

Tonic Sol-fa

).

In the sixteenth century, Hubert Waelrant replaced the Ut by a Do as he judged the ut syllable difficult to pronounce. (The Latin u

was pronounced differently by the French, Flemish, Germans, English and

others). In some countries (particularly France and Belgium) the Do (and the other syllables) became fixed replacing the orginal note names. Others have suggested that Ut was replaced by Do, the first syllable of Dominus, in 1673, at the suggestion of Giovanni Maria Bononcini.

|

| 3 | The Hexachord

esacordo (Italian m.), Hexachord (German m./n.), hexacorde (French m.), hexacordo (Spanish m.)

The solmisation syllables were applied to sequences of six notes (e.g. C - D - E - F - G - A) called hexachords (Greek:

hexa

= six,

chorde

= string or note).

There are three hexachords starting on the notes g, c and f.

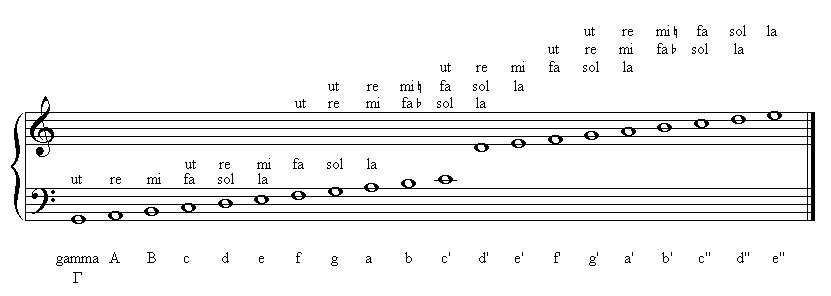

The note letter names of the upward scale from gamma ut then read

gamma, A, B, c, d, e, f, g, a, b, c', d', e', f', g', a', b', c'', d'', e''

Having chosen the name of the bottom note and defined the sequence

from there upwards, all the others follow. With a five line per stave

arrangement, the line between the staves in C, which, in medieval times, was called c sol fa ut, is today called middle C. Notes are named from bottom to top - i.e. sol fa ut rather than ut fa sol. The extensions sol fa ut describe the position of this particular c in the progression of hexachords, starting on gamma ut, then restarting a fourth higher (c fa ut), and finally starting a fourth above that (f fa ut) after which the sequence begins again on the g one octave above gamma.

In order to maintain the correct intervallic relationship within each hexachord, the hexachord starting on f has a b flat (b rotundum) for fa while the hexachord starting on g has a b natural (b quadrum) for mi. This produces two different Bs, B fa and B mi, which are a semitone apart.

In order to maintain the correct intervallic relationship within each hexachord, the hexachord starting on f has a b flat (b rotundum) for fa while the hexachord starting on g has a b natural (b quadrum) for mi. This produces two different Bs, B fa and B mi, which are a semitone apart.

The hexachords on f, g and c were termed 'soft' (molle), 'hard' (durum) and 'natural' respectively.

These mediaeval terms have persisted in German with the naming of keys, namely dur (German: hard - for major) and moll (German: soft - for minor), and the convention for naming the notes b flat and b natural which are called respectively B and H.

As it happens, middle C, lies just about in the middle of

the standard piano keyboard and for this reason most pianists assume

that the description 'middle' is a reference to this accident of piano

manufacture. The term 'middle' is applied only to the note c and not to the register within which it lies.

Reference:

Hexachords, Solmization, and Musica Ficta

Note:

solmization systems have developed in other parts of the world. In India the syllables, called sargam, are sa, ri, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni.

|

|

Helmholtz Pitch Notation

::

|

Key word:

distinguishing octaves |

| 1 |

Helmholz Pitch Notation

If you look at the note names below the stave in the example

above, you will notice that the first two note names after gamma are

shown capitalised (A and B), the next seven note names (from c to b) are in lower case, that the seven note names after that (from c' to b') have a single prime ' (other writers may use superscript i), and the final three note names (from c" to e") have a double prime '' (other writers may use superscript ii, or small numbers - ii would then be 2).

Helmholtz notation describes an octave as a series of notes starting with the note name c (thus, c, d, e, f, g, a, b) with different octaves being distinguished by the use of upper and lower case and sometimes subscript or superscript prime (') or i.

| the key to Helmholtz Pitch notation, using i rather than prime, is that: |

| a Helmholtz scale always starts on a c |

|

B is the note immediately below c while b is the note immediately below | ci |

|

the note c in the different octaves are shown by the sequence:

Cii, Ci, C, c, ci, cii, ciii

or, in Sweden for example:

C2, C1, C, c, c1, c2, c3 |

|

in the 'so-called' German method, the note middle C is denoted by the letter c with a horizontal line lying above it, each octave above that bears an additional horizontal line. Thus:

|

|

| some authors write Ci as CC, Cii as CCC and Ciii as CCCC (see, however, English Octave-Naming Convention below) |

| the note c two ledger lines below the bass clef is C |

| the note 'middle c' is ci |

| the note 'gamma ut' (Γ ut) in Guido d'Arezzo's system (the bottom line of the bass clef) is G in Helmholtz' notation |

Helmholtz developed this system in order to accurately define pitches in his classical work on acoustics Die Lehre von den Tonempfindungen als physiologische Grundlage für die Theorie der Musik (1863), translated into English by A. J. Ellis as On the Sensations of Tone

(1875). Today, Helmholtz notation is used widely by scientists

and doctors when discussing the scientific and medical aspects of sound

in relation to the auditory system.

Helmholtz notation may be used also to distinguish octaves.

The octave from lower case c to b is called the 'small octave' while that from c' to b' is called the 'one-line octave', 'one-line' referring to the single prime '

or, using what was once called 'the German method', to a horizontal

line placed across the top of note name (see table below). The next

octave c'' to b'' is called the 'two-line octave' (in the

German method two horizontal lines are placed above the note name) and

so on upwards. The octave written with capital letters, C to B is the 'great octave'.

|

|

English Octave-Naming Convention

::

|

Key word:

distinguishing octaves |

| 1 |

English Octave-Naming Convention

A source of confusion when using the multiple C octave notation is the

fact that some authors, particularly English authors writing about the

organ, use a different convention for CC which they associated with C two leger lines below the bass staff, CCC for C an octave lower and CCCC for the C two octaves lower. CC

is generally the lowest note on the manuals of an organ and is called

an 8 ft. note because that is the length of an open pipe required to

produce it. As pitch drops an octave as a pipe is doubled in length so CCC is called a 16 ft. note and CCCC

is called a 32 ft. note. Another feature that distinguishes the

English octave-naming convention from that of Helmholtz (see above) is

that each octave runs from G to the F seven notes above. In this

regard, it follows the convention adopted by Guido d'Arezzo where each

octave is named from gamma ut, the G on the bottom line of the

bass staff. Helmholtz's octaves, of course, run from C to the B above.

Two particular octave names that follow the English system are in alt (G above the treble stave to the F above, inclusive), and in altissimo (the octave above in alt).

|

|

Franco-Belgic Octave-Naming Convention

::

|

Key word:

distinguishing octaves |

| 1 |

Franco-Belgic Octave-Naming Convention

The Franco-Belgic note naming system sets the C two leger lines below the bass clef as Do1, Do uno or Do primera.

Each C one octave higher is named by increasing the subscript number by 1. So, middle C is Do3, while C two leger lines above the treble clef is Do5.

The note a' (in the Helmholtz system), which is used to set pitch, is La3 in the Franco-Belgic system.

The system that uses letters of the alphabet to name the different pitches is called, by the French, Notation allemande et anglo-saxonne (German and Anglo-Saxon notation).

|

|

Scientific Pitch Notation

::

|

Key word:

distinguishing octaves |

| 1 |

Scientific Pitch Notation/Note-Octave Notation/American Standard

| an alternative naming convention called 'Scientific Pitch Notation', 'Note-Octave Notation' or American Standard Pitch Notation: |

| the lowest c on a grand piano is named C1 (alternatively C1, C(1), C[1] or C1) |

| notes in the octave below C1 have their appropriate note name followed by the number 0 |

| notes lying between C1 and the note one octave higher (written C2, C(2), C[2] or C2) have their appropriate note names followed by the number 1 |

| each succeeding octave above that advances the number by one |

| on a piano 'middle c' is C4, C(4), C[4] or C4 |

| the note a whose pitch is set by international standard is A4, A(4), A[4] or A4 |

| C4 is equivalent to ci in Helmholtz notation |

| the note 'gamma ut' (Γ ut) in Guido d'Arezzo's system (the bottom line of the bass clef) is G2 in Scientific Pitch notation |

Note that the symbol Cb4 means "the pitch one semitone (chromatic step) below the pitch C4" and not "the pitch-class Cb in octave 4." Thus, Cb4 is the same pitch as B3, not B4.

The letter name is first combined with the Arabic numeral to determine a

specific pitch, which is then altered by applying accidentals. For this

reason, the notation C4b would be slightly more consistent, though significantly less legible.

|

|

Naming the Octaves

::

|

Key word:

distinguishing octaves |

| 1 |

Naming the Octaves

octave, ottava (Italian f.), Oktave (German f.), octave (French f.), octava (Spanish f.)

The convention for naming octaves is fairly arbitrary but can be useful

when considering how chords, that is groups of notes played together,

sound. Keeping the notes well spread apart significantly strengthens

the effect of a chord. We illustrate one naming convention below. Each

note

C

is said to be in a different

register.

|

scientific pitch notation

|

Helmholtz pitch notation

|

frequency (where A4, ai = 440 Hz)

|

octave name

|

C0 - B0

C(0) - B(0)

C[0] - B[0]

C0 - B0

|

Cii - Bii

C2 - B2

CCC - BBB

|

16.352 Hz - 30.868 Hz

|

sub-contra octave

Subkontra-Oktave (German)

double contre-octave (French)

|

| C1 is called 'double pedal C' |

C1 - B1

C(1) - B(1)

C[1] - B[1]

C1 - B1

|

Ci - Bi

C1 - B1

CC - BB

|

32.703 Hz - 61.735 Hz

|

contra octave

Kontra-Oktave (German)

contre-octave (French)

|

| C2 is called 'pedal C' |

C2 - B2

C(2) - B(2)

C[2] - B[2]

C2 - B2

|

C - B

|

65.404 Hz - 124.47 Hz

|

great octave

Große-Oktave (German)

grande octave (French)

|

| C3 is called 'bass C' |

C3 - B3

C(3) - B(3)

C[3] - B[3]

C3 - B3

|

c - b

|

130.81 Hz - 246.94 Hz

|

small octave

Kleine Oktave (German)

petite octave (French)

|

| C4 is called 'middle C', do centrale (Italian), eingestrichenes c (German), do central (French, Spanish) |

C4 - B4

C(4) - B(4)

C[4] - B[4]

C4 - B4

|

ci - bi

c1 - b1

c' - b'

|

261.63 Hz - 493.88 Hz

|

one-line octave

or

one-accented octave

or

once-accented octave

Eingestrichene Oktave (German)

2me petite octave (French)

|

| C5 is called 'treble C' |

C5 - B5

C(5) - B(5)

C[5] - B[5]

C5 - B5

|

cii - bii

c2 - b2

c'' - b''

|

523.25 Hz - 987.77 Hz

|

two-line octave

or

two-accented octave

or

twice-accented octave

Zweigestrichene Oktave (German)

3me petite octave (French)

|

| C6 is called 'top C' |

C6 - B6

C(6) - B(6)

C[6] - B[6]

C6 - B6

|

ciii - biii

c3 - b3

c''' - b'''

|

1046.5 Hz - 1975.5 Hz

|

three-line octave

or

three-accented octave

or

thrice-accented octave

Dreigestrichene Oktave (German)

4me petite octave (French)

|

| C7 is called 'double top C' |

C7 - B7

C(7) - B(7)

C[7] - B[7]

C7 - B7

|

ciiii - biiii

c4 - b4

c'''' - b''''

|

2093.0 Hz - 3951.1 Hz

|

four-line octave

or

four-accented octave

Viergestrichene Oktave (German)

5me petite octave (French)

|

| C8 is called 'triple top C' |

C8 - B8

C(8) - B(8)

C[8] - B[8]

C8 - B8

|

ciiiii - biiiii

c5 - b5

c''''' - b'''''

|

4186.0 Hz - 7902.2 Hz

|

five-line octave

or

five-accented octave

Funfgestrichene Oktave (German)

6me petite octave (French)

|

Scientific Pitch Notation has been used to name the notes in the MIDI chart below.

Many domestic pianos, electronic keyboards and the like have

ranges smaller than that of a full concert grand. These small range

keyboards are called 'short' keyboards. Counting the notes on a 'short'

keyboard will not be an appropriate way of working out the Scientific

Pitch names of notes; for this reason, we favour Helmholtz notation

(described immediately above).

|

|

MIDI

::

|

Key word:

MIDI protocol

General MIDI

patch bank

note number mapping |

| 1 |

MIDI

The MIDI protocol is a music description language in binary form.

Each action of musical performance is assigned a specific standardised

binary code or 'instruction'. Because MIDI was designed originally for

keyboards many of the actions are percussion oriented. To sound a note

in MIDI language you send a "Note On" message. Assigning that note a

"velocity" determines how loud it plays. Other MIDI messages include

selecting which instrument to play, mixing and panning sounds, and

controlling various aspects of electronic musical instruments. From the

moment the MIDI 1.0 Standard was finalized in the early 1980s it was

clear that certain matters had been overlooked. There was no

specification for the way patch numbers were assigned to particular

instruments, at least not until Roland proposed an addendum to MIDI 1.0

called General MIDI (or GM) in the late 1980s. By creating a stand

'patch bank' the user could be certain that each of the 128 patches

produced the sound specified, whether it might be a Grand Piano (patch

1) or a Nylon String Guitar (patch 25).

There were also deviances in regards to Note Number mapping. For

example, some manufacturers mapped middle 'C' to MIDI Note Number 60

(see the diagram below). However, others mapped it to Note Numbers 72 or

48. Another shortcoming in the specification was that the MIDI

standards do not designate octaves. The standard merely designates

'middle C' as being note number 60. Two octave designations have been

devised. One version of the MIDI system uses C3 to designate 'middle C'

(MIDI note 60, 261.626 Hz). That means that the octave designation for

MIDI note "0" would be "-2" or notated as C-2. A second version uses the

lowest note available to the MIDI system (MIDI note 1, 8.176 Hz) to

designate Octave "0" with the notation of C0. In this system, 'middle C'

(MIDI note 60, 261.626 Hz) is octave 5 with the notation of C5.

References:

|

|

Shape Note Notation

::

|

Key words:

solfege

Fasola

Bay Psalme Book

shaped notehead

Patentnote

Buckwheat

Southern Harmony

Sacred Harp

pitch of convenience |

| 1 |

Shape Note Notation

This is an abridged version of the information on F. Ishmael J. M. Stefanov-Wagner's site.

Solfege is a method of ear-training which uses the assignment of

syllables to degrees of the scale to assist a singer's memory of pitch.

In the European hexachord (six note) system of

Ut - Re - Mi - Fa - Sol - La, codified by Guido d'Arezzo

(990 - 1055) and used for hundreds of years, the six notes have to be

overlapped when naming a full octave. For a full description go to the

section on

middle C.

There were rules to determine from which hexachord the syllable for a given note would be sung. The continental six-note

Ut - Re - Mi

was simplified in England to the four-note system which you can see by following the scale from C to C as Fa - Sol - La - Fa - Sol - La - Mi - Fa.

[This system was known as Lancashire or Old English Sol-fa]. This is

what the English colonists brought with them when they set sail for the

New World, and upon which the early New England singing masters based

their lessons and developed their aids to reading. [It was then called

Fasola].

The Sternhold & Hopkins Psalter was first printed in England

in 1562 with melodies for 46 tunes. The printer John Windet thought that

solmization was a useful enough aid in sight-singing that the tunes in

his 1594 edition of the Sternhold & Hopkins Psalter had initials for

the syllables (

U R M F S L

) printed beneath the notes. In the foreword it was explained:

...I have caused a

new print of note

to be made with letter to be joined to every note: whereby thou

mayest know how to call every note by his right name, so that with a

very little diligence thou mayest more easilie by the viewing of these

letters, come to the knowledge of perfect solfeying... the letters be

these U for Ut, R for Re, M for My, F for Fa, S for Sol, L for La. Thus

where you see any letter joyned by the notes you may easilie call him by

his right name, ...

Across the ocean and a century later at Boston in 1698 the ninth

edition of the Bay Psalme Book (printed since 1640 with texts only)

featured the addition of 13 two-part tunes, with four-note syllables

indicated by letters printed beneath the staff. This is thought to be

the first music printed in the New World.

Cambridge Short tune from the Bay Psalme Book, 1698,

Cambridge Short tune from the Bay Psalme Book, 1698,

melody and bass, with

mi-fa-sol-la

letters printed beneath the staff.

The diamond shaped notes were standard musical

notation at that time.

Rev. John Tufts

An Introduction to the Singing of Psalm-Tunes in a Plain & Easy Method

first appearing between 1714 and 1721 had the further innovation of printing the initial letters (

M-F-S-L

) on the staff

in place of

the note-heads. Durations are indicated by the extra dots to the

right of the letter - each dot doubles the length of the note.

Westminster, in three parts with new notation by John Tufts.

Westminster, in three parts with new notation by John Tufts.

Printed in Boston. From the edition of 1727.

The first book printed with shaped noteheads, using "patent notes" was the

Easy Instructor,

by Wm. Smith and Wm. Little in 1801. The shapes used then are still in use to this day:

Andrew Law's

The Musical Primer

of 1803, used similar shaped notes but interchanged somewhat from

the assignments of Smith & Little and without the customary

five-line staff. [American notations where different note-head shapes

were associated with different syllables is known as 'Patentnote' or

'Buckwheat' notation.]

By 1815 in Boston the fuguing tunes, shape-notes and the fa-sol-la

solmization that facilitated them had become (so the reformers thought)

obsolete and interest in them was maintained primarily to the far south

and west.

By 1815 in Boston the fuguing tunes, shape-notes and the fa-sol-la

solmization that facilitated them had become (so the reformers thought)

obsolete and interest in them was maintained primarily to the far south

and west.

In these parts of the country though, the hymns and music were

taken to heart and survive to this day. One such example is William

Walker's Southern Harmony, first printed in New Haven in 1835, revised

several times and there are those who still sing from a current printing

of a facsimile editions of the version of 1854. Another is Benjamin

Franklin White's

Sacred Harp,

first published in 1844, most recently revised in 1991. The Fasola

tradition, which uses shape note notation, is one of unaccompanied

singing, that is, without any assistance by instruments.Thus when

singing shape-note hymns it is the practice first to "sing the notes",

that is, to sing the fa-sol-la syllables corresponding to the shapes in

the music before singing the text. This serves to set the tune in memory

and enables persons to more easily sight-read previously unseen or

unheard music.

Tunes are sung in relative pitch, rather than at an absolute pitch

derived from A=440Hz.; referred to as " Pitch of Convenience", a long

standing tradition as can be seen from

directions for setting the first Note

from the Bay Psalm Book.

References:

|

|

Tonic Sol-fa

::

|

Key words:

J. S. Curwen

Sarah Glover

Langue de durées

Tonic Sol-fa

Curwen Institute

functional solmization

Galin-Paris-Chevé

fixed do solfeggio

moveable do solfeggio |

| 1 |

Tonic Sol-fa

In 1840s England, J. S. Curwen (1816-1880) introduced a system,

earlier developed by Sarah Glover of Norwich (1785-1867) in her Scheme for Rendering Psalmody Congregational (1835), which was designed to help in the sight-reading of music. The system was called the

Tonic Sol-fa method. Curwen's method later incorporated French time names (derived from Aime Paris's

Langue de durées

) and devised pitch hand signs which, in a modified form, are

familiar to contemporary music teachers as part of the popular Kodály

method.

John Curwen was an English congregational minister and he had

taught himself to read music using Sarah Glover's book as an

introduction to the idea of

Tonic Sol-fa. Religious and social ideals of equality

motivated him to create and promulgate an entire method of teaching

based on this idea, for he believed that music should be the inheritance

of all classes and ages of people. At considerable expense to himself,

he published his own writings, which included a journal entitled

Tonic Sol-fa Reporter and Magazine of Vocal Music for the People.

After

1864 he resigned his ministry to devote most of his time to what had

become a true movement in mass music education. He and his son John

Spencer Curwen incorporated a publishing firm, J. Curwen & Sons,

eventually adding

Tonic Sol-Fa Agency

to its name. It became an important publisher of educational

music. In 1869 John Curwen established the Tonic Sol-Fa College, which

just over 100 years later established the Curwen Institute in London.

Though Curwen did not truly invent

Tonic Sol-fa, he developed a distinct method of applying it

in music education, one that included both rhythm and pitch. William

McNaught, a devoted student of the Tonic Sol-fa Method, is said by his

son to have thought of it as "musicianship of the mind with the voice as

its instrument."

You may remember that middle 'c' is named 'sol fa ut' in medieval

music theory (see above) and that the 'c' one octave above 'middle c' is

named 'sol fa'. It is from these two syllables 'sol' and 'fa' that the

system derives its name and explains the presence of the hyphen between

'sol' and 'fa'. The essence of the Curwen system is that the key-note

(or tonic) is called 'doh'. It is followed, in an ascending major scale,

by the notes 'ray', 'me', 'fah', 'soh', 'lah', 'te' before returning to

'doh', one octave higher than the first 'doh'. 'doh' is moveable - in

other words, it depends on the key in which the piece of music is set,

which note will be 'doh'. In fact, 'doh' is always the key-note.

Curwen's system, called functional solmization,

uses names to describe a note's function (tonic, dominant, etc.) rather

than its pitch, and contrasts with the continental system where 'doh'

is immoveable and always represents the note 'c' whatever the key in

which the piece of music is written.

Curwen's note names are actually no more than an anglicised form

of Guido d'Arezzo's nomenclature with 'doh' replacing 'ut' and the

addition of 'te' for the seventh note of the scale which is otherwise

absent because d'Arezzo names only the six notes of the hexachord.

An apparent disadvantage is a lack of chromatic notes or any distinction between the same note but in different octaves.

Here Curwen appears to have turned to the Galin-Paris-Chevé moveable do system named after Pierre Galin [Exposition d'une Nouvelle méthode

(1818)] and Émile-Joseph Chevé (1804-1864), Chevé's wife Nanine Paris

and Nanine's brother Aimé Paris (1798-1866) [E. Chevé (Mme Nanine Paris)

Méthode élémentaire de musique vocale (1864); E. Chevé (M. & Mme) Méthode élémentaire d'harmonie (1846); E. Chevé (M. & Mme) Exercices élémentaires de lecture musicale à l'usage des écoles primaires (1860)].

This system named the notes of an ascending major scale, starting on the tonic, with the numerals 1-7.

0 denotes a rest.

The

use of numerals harks back to a suggestion made in 1742 by Jean-Jacques

Rousseau although the idea was not new. Similar proposals had been

made by in France by Jean Jacques Souhaitty (1667) and in England by

William Braythwaite (1638). The Galin-Paris-Chevé system used dots

placed above or below a numeral to identify the octave of that

particular note. Other schemes included ticks, or different cases or

print styles. Today, scale syllables have become more standardised and

include chromatic notes.

| in 'fixed do' solfeggio, the notes of the chromatic scale are named using the solfeggio or Latin names which in French, English, Italian and German are: |

| rising or ascending scale |

| C | C# | D | D# | E | F | F# | G | G# | A | A# | B natural

H (German) | c |

do

ut (French) | di | re

ré (French) | ri | mi | fa | fi | sol

so (English) | si | la | li | ti

si (Continent) | do

ut (French) |

| falling or descending scale |

| c | B natural

H (German) | B flat

B (German) | A | Ab | G | Gb | F | E | Eb | D | Db | C |

do

ut (French) | ti

si (Continent) | te | la | le | sol

so (English) | se | fa | mi | me | re

ré (French) | ra | do

ut (French) |

Some writers call the Aretinian or solfeggio syllables

'Italian' when they are actually derived from a verse in 'Latin' from

syllables of which Guido d'Arezzo took his note names, with some

additions and modifications as noted above (for example replacing si with ti for B natural).

Using a 'moveable do' system, full chromaticism is not needed,

because a tune is normally re-notated into each new key, by

re-positioning the do (or ut in French), even if that key lasts only for a few bars. Some, however, hold to the view that using

Tonic Sol-fa with full chromaticism loses the advantages of

simplicity and readability. In this case no distinction is made

between chromatic notes. So G flat, G natural and G sharp are all named sol under solmisation although the correct inflection is used when naming notes other than under solmisation, i.e. sol bemolle (G flat), sol (G natural) and sol diesis (G sharp). In Italy, as in other parts of Continental Europe, when chromatic names are not being used, many teachers use si not for G sharp but, as in the modified Latin system, for B natural.

References:

Musical Polyglottery

by Dr. Jennifer Paull - non-standard music notation in the world's classrooms

Music: The Chameleon Catalyst

by Dr. Jennifer Paull - music as a tool with many uses (e.g. using musical theory to help students with learning disorders)

These two articles and further essays about music are included in the Jennifer Paull's anthology Cathy Berberian and Music's Muses.More information about this book can be found on Dr Paull's website http://www.amoris.com/books/index.html.

Links about Music Notation

|

|

OZ Pitch-Naming Convention

::

|

Key word:

Oz |

| 1 |

OZ Pitch-Naming Convention

An alternative pitch-naming convention has been proposed whereby the

letters O through Z are used to indicate the twelve pitches of the equal

tempered scale and numerals 0 through 9 are used to indicate octaves.

This convention is given the name OZ (pronounced "ahz").

For more detail information, please refer to the link below.

Reference:

The OZ Pitch-Naming Convention

|

|

Integer Notation

::

|

Key word:

Integer Notation |

| 1 |

Integer Notation

Answers.com's excellent article on music notation includes information about integer notation from which we have quoted below.

In integer notation, or the integer model of pitch, all pitch classes

and intervals between pitch classes are designated using the numbers 0

through 11. It is not used to notate music for performance, but is a

common analytical and compositional tool when working with chromatic

music, including twelve tone, serial, or otherwise atonal music. Pitch

classes can be notated in this way by assigning the number 0 to some

note - C natural by convention - and assigning consecutive integers to

consecutive semitones; so if 0 is C natural, 1 is C sharp, 2 is D

natural and so on up to 11 which is B natural. The C above this is not

12, but 0 again (12-12=0). Thus arithmatic modulo 12 is used to

represent octave equivalence. One advantage of this system is that it

ignores the "spelling" of notes (B sharp, C natural and D double-flat

are all 0) according to their diatonic functionality.

There are a few drawbacks with integer notation. First, theorists have

traditionally used the same integers to indicate elements of different

tuning systems. Thus, the numbers 0, 1, 2, ... 5, are used to notate

pitch classes in 6-tone equal temperament. This means that the meaning

of a given integer changes with the underlying tuning system: "1" can

refer to C# in 12-tone equal temperament, but D in 6-tone equal

temperament. Second, integer notation does not seem to allow for the

notation of microtones, or notes not belonging to the underlying equal

division of the octave. For these reasons, some theorists have recently

advocated using rational numbers to represent pitches and pitch classes,

in a way that is not dependent on any underlying division of the

octave. See the articles on pitch and pitch class for more information.

Another drawback with integer notation is that the same numbers are used

to represent both pitches and intervals. For example, the number 4

serves both as a label for the pitch class E (if C=0) and as a label for

the distance between the pitch classes D and F#. (In much the same way,

the term "10 degrees" can function as a label both for a temperature,

and for the distance between two temperature.) Only one of these

labelings is sensitive to the (arbitrary) choice of pitch class 0. For

example, if one makes a different choice about which pitch class is

labeled 0, then the pitch class E will no longer be labelled "4."

However, the distance between D and F# will still be assigned the number

4. The late music theorist David Lewin was particularly sensitive to

the confusions that this can cause.

|

|

:: next lesson :: next lesson

|

|

:: next lesson

:: next lesson

:: next lesson

:: next lesson